By Abdulrasheed Hammad

For many Nigerian youths, the biggest obstacle to education and employment is no longer exams or qualifications, but broken digital systems. From UTME glitches and university portal failures to NYSC registration and biometrics errors and collapsed recruitment platforms, a single system error delays graduation, denies and frustrates national service and shuts young people out of jobs. In this report, Hammad Abdulrasheed exposed how persistent ICT failures have turned Nigeria’s digital promise into a barrier and the growing human cost of a system that keeps locking its youth out.

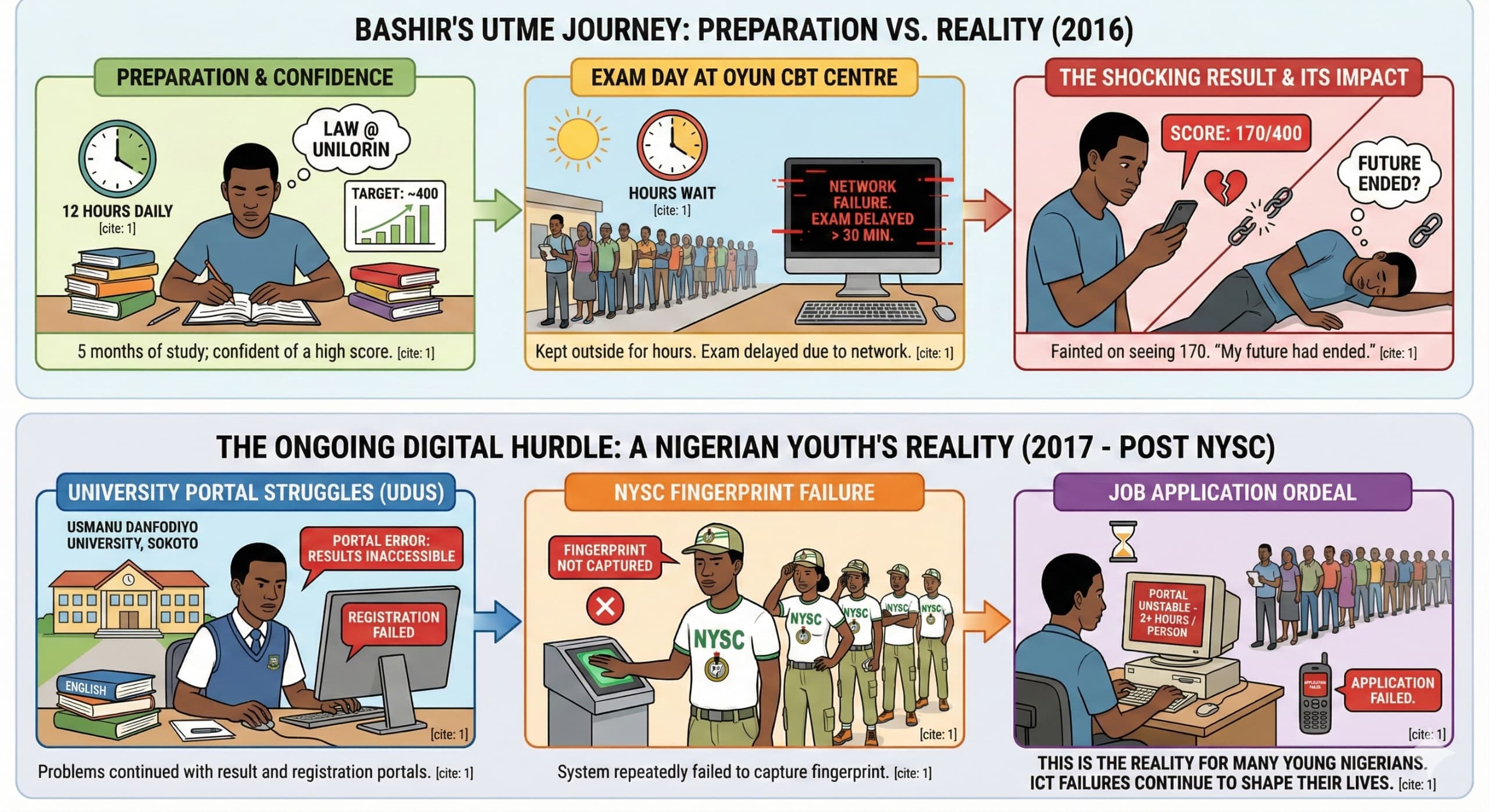

In 2016, Bashir Adeleke spent five months preparing for the UTME because he wanted to study Law at the University of Ilorin. He read for about 12 hours every day, covering the syllabus and practising past questions. By the time he went for the exam, he was confident he had done enough to score close to 400, the highest possible mark.

On the exam day at the JAMB CBT centre in Oyun, Ilorin, Kwara State, candidates were kept outside for hours. When they were finally allowed in, the exam could not start immediately because of network problems. After more than 30 minutes of delays, they eventually wrote the exam. When Adeleke later checked his result and saw 170 out of 400, he fainted. “The questions were simple. I knew what I wrote,” he said. “Seeing that score felt like my future had ended. I had sacrificed everything for that exam, and people believed in me.”

His experience mirrored what many candidates faced in 2016. That year’s UTME was disrupted by widespread ICT and logistical failures across CBT centres in Nigeria. Candidates reported system crashes, network disruptions, faulty computers, incomplete questions, power outages, and inconsistent results. Some candidates received different scores at different times. JAMB later admitted that technical problems affected the exam. While 40 marks were added to the scores of some candidates, many others were ignored, and no one was held accountable. Thousands of candidates were left with results that did not reflect their performance.

The glitch changed the direction of Adeleke’s life. He lost hope of studying Law and later gained admission to study English Language and Literary Studies at Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto, in 2017. The problems followed him there. He struggled with registration portals and often could not access his results.

The National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) is a compulsory one-year programme for Nigerian graduates under 30, created to promote national unity. It includes orientation camp, a year of work assignment, and community service. An NYSC discharge or exemption certificate is required for most jobs and further studies in Nigeria.

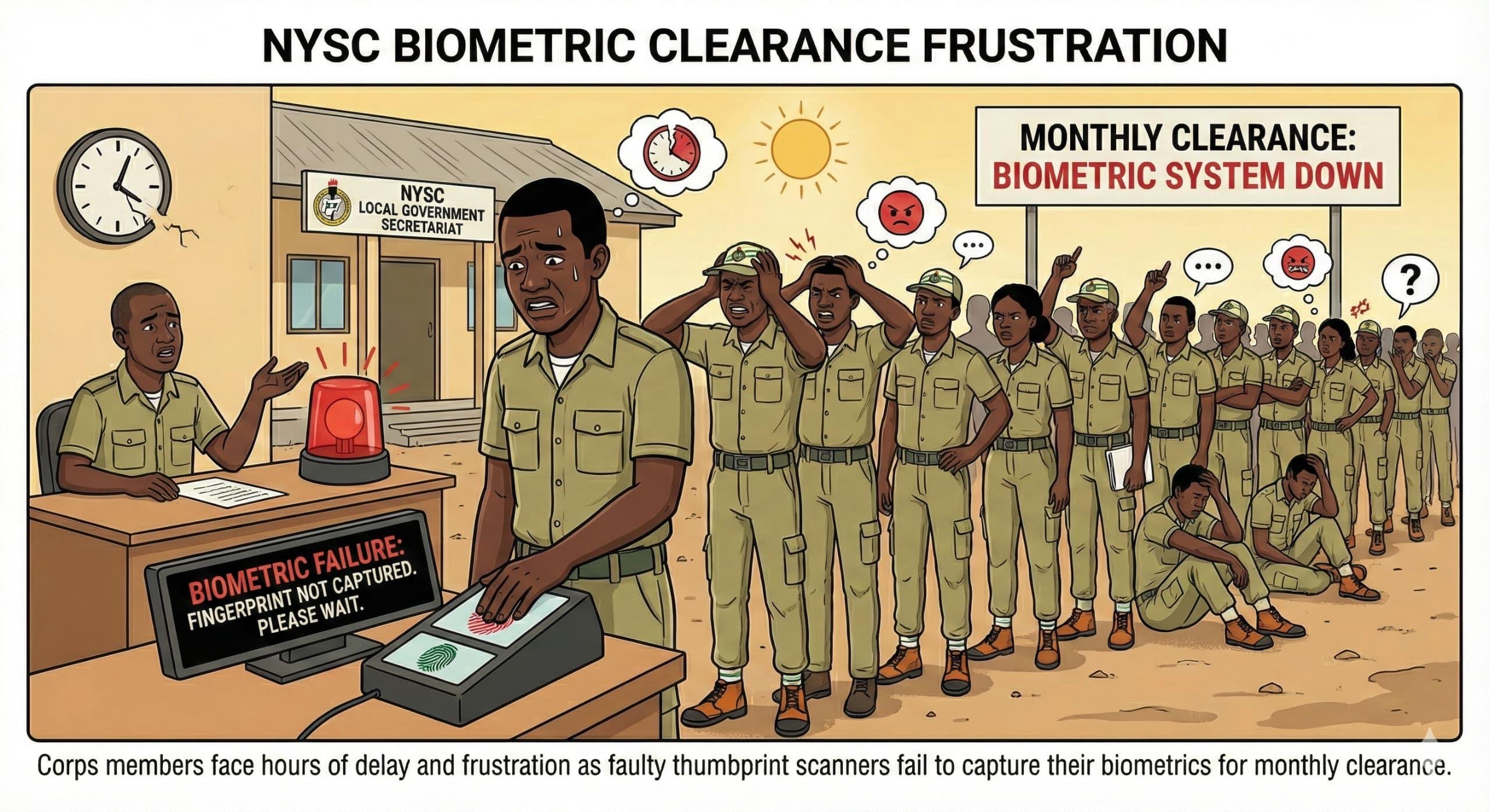

During NYSC registration, the biometric system repeatedly failed to capture his fingerprint. After NYSC, the same issues appeared again. While applying for a job under the Civil Defence, Correctional, Fire and Immigration Services Board, he could not complete the application on his phone and had to go to a cybercafé. Because the portal was slow and unstable, it took more than two hours to register a single person, forcing him to spend hours in a queue before he succeeded.

Corps members face delays during monthly clearance as fingerprint machines fail to capture their fingerprints

This is the reality for many young Nigerians. From entrance examinations to university registration, NYSC enrolment, and job applications, ICT failures continue to shape their lives. For many, these problems do not happen once. They follow them at every stage, quietly limiting their chances and delaying their future.

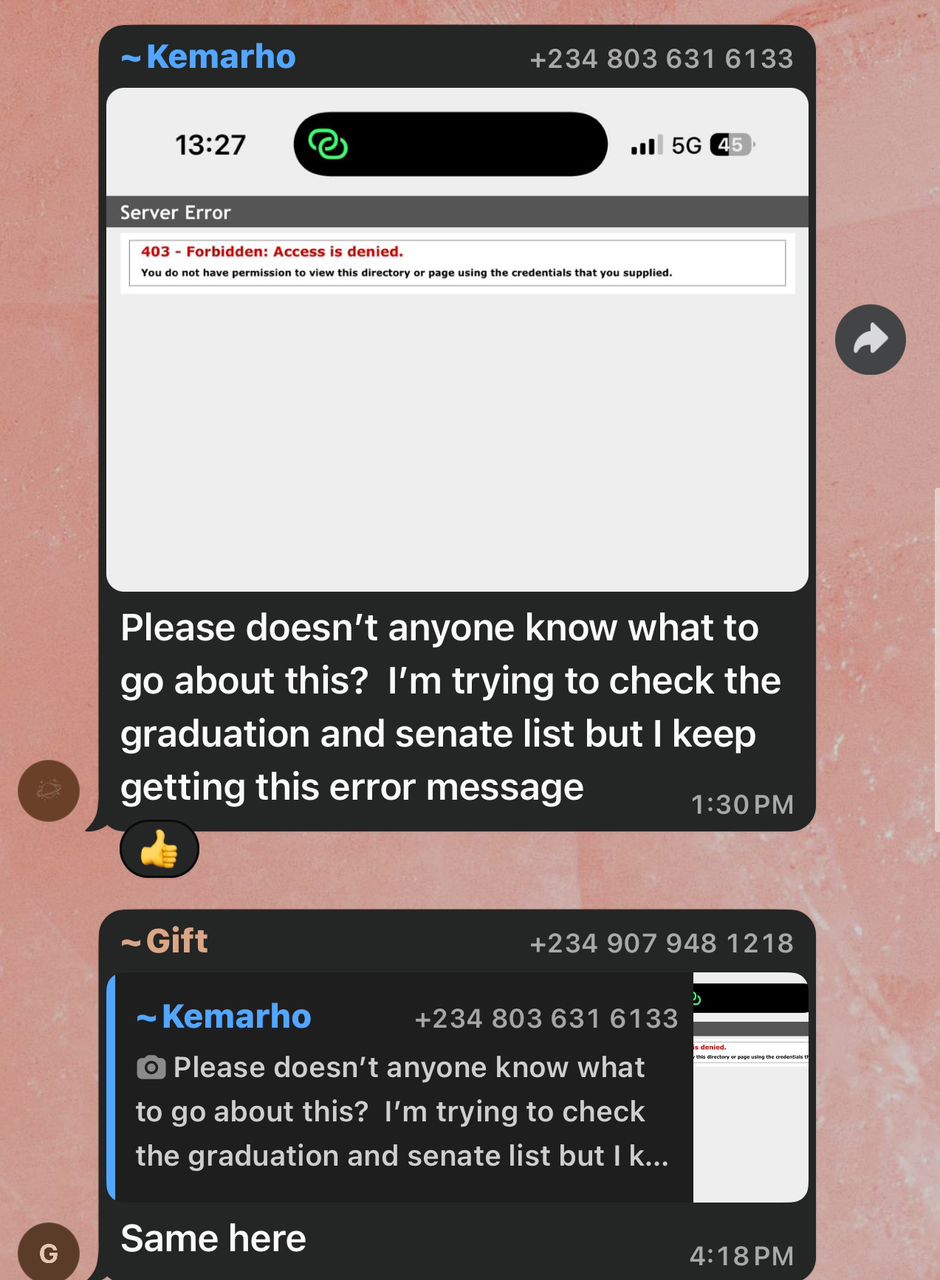

NYSC portal showing errors

NYSC portal showing errors

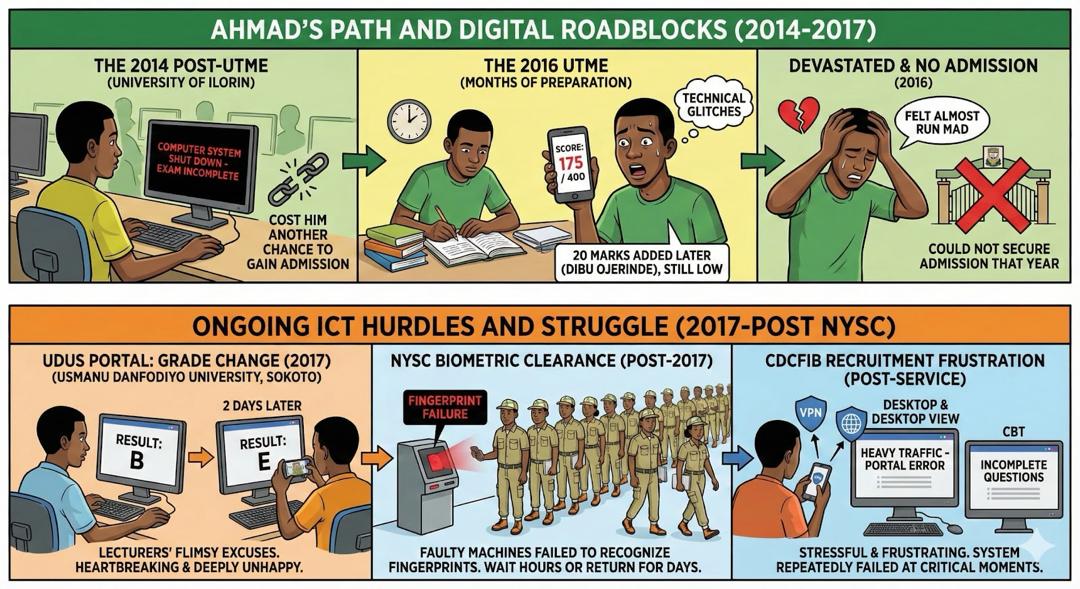

Ahmad Abdulkareem faced a similar experience. He sat for the 2016 UTME after months of preparation, only to score 175 out of 400, a result he said left him devastated and almost run mad. Days later, JAMB, under the leadership of then registrar Dibu Ojerinde, added 20 marks to his score, but it was still far below what he believed he deserved. That was when he became aware that technical glitches had affected the examination. He could not secure admission that year. In 2014, while writing Computer-Based-Test post-UTME at the University of Ilorin, his computer system shut down before he could complete the exam, costing him a chance to gain admission into his desired course that year.

The challenges continued at Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto, where he eventually gained admission to study Political Science in 2017. As a 100-level student, he checked his result and saw a B in one of his courses, only to discover two days later that the grade had changed to an E. “I had to start taking screenshots of my results,” he said. “When I complained, the lecturers gave flimsy excuses. It was heartbreaking, and I was deeply unhappy.” During NYSC, biometric thumb-printing for monthly clearance became another struggle, as faulty thumbprint machines often failed to recognise corps members’ fingerprints, forcing them to wait for hours or return for days.

Frustrated corps members queue for monthly clearance at the NYSC Secretariat, Wuse Zone 3, Abuja

Frustrated corps members queue for monthly clearance at the NYSC Secretariat, Wuse Zone 3, Abuja

After service, the same pattern followed him into job applications. During the Civil Defence, Correctional, Fire and Immigration Services Board (CDCFIB) recruitment, he struggled to access the portal due to heavy traffic. Many applicants, he said, resorted to using VPNs or switching to desktop view on their phones just to log in. The CBT test was equally problematic, with some candidates facing incomplete questions and others unable to load the exam properly. “It was stressful and frustrating,” he said, describing a system that repeatedly failed applicants at critical moments in their lives.

A frustrated corps member after a thumbprint machine failed to capture her fingerprints at the NYSC Secretariat, Wuse Zone 3, Abuja FCT.

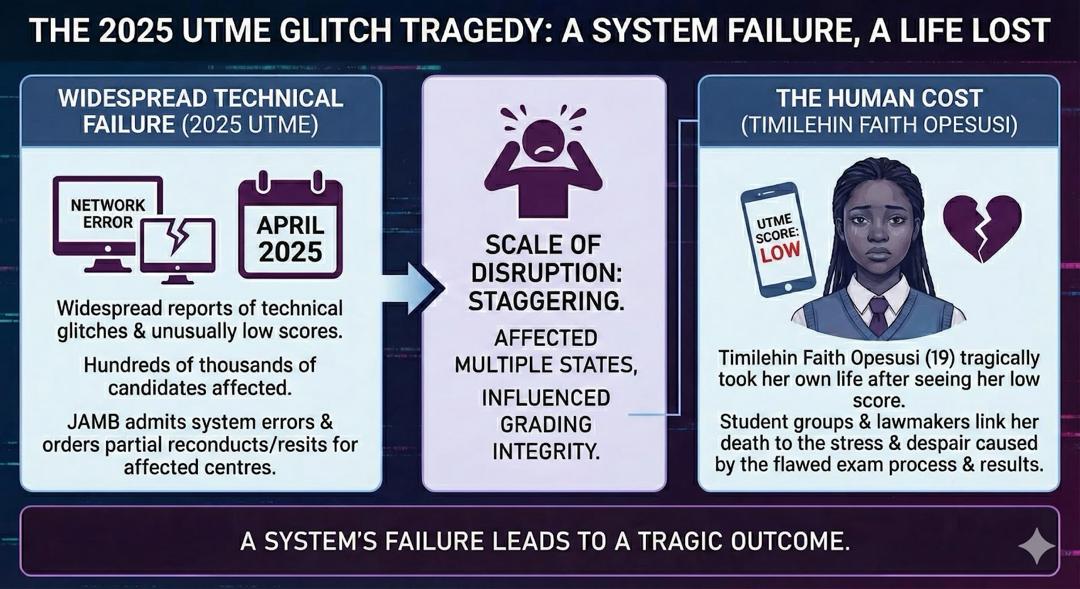

The 2016 UTME glitches reoccurred in 2025, costing a student’s life

In 2025, the release of the UTME results was followed by widespread reports of technical glitches and unusually low scores affecting hundreds of thousands of candidates, leading to outrage and a decision by JAMB to reschedule exams for those affected after admitting errors in its system. Amid that controversy, a 19-year-old UTME candidate, Timilehin Faith Opesusi, tragically took her own life after seeing her low score, an outcome that student groups and lawmakers linked directly to the stress and despair caused by the flawed exam process and its results.

The Registrar, Professor Ishaq Oloyede, publicly admitted problems that affected hundreds of thousands of candidates and ordered partial reconducts/resits for affected centres. The scale of the disruption was staggering: JAMB said the glitch affected centres across several states and influenced the grading or integrity of results for many candidates.

Habeebullah Issa said he was also affected by the 2016 UTME glitches, which left him with a low score like many other candidates that year. Although he later gained admission to study Law at the University of Ilorin many years later, the digital problems followed him. He also recalled struggling to pay his school fees on time because he could not access the university portal.

After graduating from UNILORIN and moving on to the Nigerian Law School, he encountered similar issues. He said the qualifying exam card he printed online carried the name of a different school. The second issue occurred when he was first posted to the Kano Campus, but when he checked again two weeks later, his posting had been changed to Abuja without any explanation.

Ali Abdulmuiz, a Common Law graduate of the University of Ilorin, also said portal problems were a regular experience. He explained that students often struggled to access the hostel registration portal, with school officials frequently blaming the issues on heavy traffic. In many cases, he said, students were assigned hostels different from the ones they selected during registration.

Uchenna Emelife said the 2016 UTME left a lasting mark on him. It was his second attempt after Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria denied him admission the first time, despite having a combined UTME and post-UTME score of 251. In 2016, he had more time to prepare because he had finished secondary school and was not working.

“Yet, the result came out as 169,” he said. “I was shocked. My parents, siblings, and friends were shocked too. It was unbelievable.” He said he tried to move on like many Nigerians do, but mentally, he could not. “It made me doubt myself. I started questioning my abilities and struggling with imposter syndrome,” he said. The following year, he enrolled in a UTME lesson centre to test himself and scored 267. “That was when I knew something was wrong in 2016 and it wasn’t me. 251 in 2015, 169 in 2016, and 267 in 2017—it didn’t add up,” he said, describing it as one of the worst injustices to work hard and fail because of factors beyond one’s control.

Victoria Mbachirin said she faced a similar experience in 2016. After the exam, she began to doubt her ability, while some classmates mocked her quietly. Many people did not believe she failed, forcing her to spend an extra year at home preparing again. “My system shut down suddenly during the exam,” she said. “I didn’t even submit. I was told nothing would happen—but something happened.” She said Nigeria needs serious improvement in its education system.

Francis Ikuerowo said his experience also confirmed that something went wrong in 2016. After scoring 282 in 2017, he became convinced that his 2016 result did not reflect his effort. He had expected over 300 and said the outcome weakened his morale. He channelled his frustration into his O-level exams and recorded distinctions in his core subjects. Reflecting on the 2025 UTME glitches, he said, “Almost a decade later, JAMB hasn’t changed.”

Hayatullahi Mudathir said his experience was no different from many others. It took him four days to complete his NYSC registration because the portal kept failing, even though there was a fixed deadline. At first, he could not receive the email needed to proceed. When he finally registered, payment became another problem, as the system would not move to the next stage.

Image of the NYSC portal not accessible

Image of the NYSC portal not accessible

He said the same thing happened again this year while registering his siblings. The process took another four days and the deadline had to be extended. At different stages, the portal stopped responding, forcing them to switch servers to link with the NYSC portal. Payments through Remita often showed blank pages until the final day of registration. “I suffered again this year,” he said.

As a former student of Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto, who often helped others pay school and hostel fees online, Mudathir said portal failures were common. According to him, the situation usually worsened when results were released or hostel allocations were announced, disrupting the entire system.

He recalled a recent case where he paid for hostel accommodation and received a Remita receipt, but the hostel allocation did not reflect on the portal until three days later. Despite reporting the issue to the Management Information System (MIS) unit, which promised to fix it within two hours, it took three days.

Mudathir also said the Civil Defence, Correctional, Fire and Immigration Services Board (CDCFIB) application process was difficult because of heavy traffic on the portal. In one instance, while helping someone apply, they could not upload the required documents before the deadline due to network errors and server glitches.

It took Abubakar Idris several days of tiredness to complete his NYSC registration. For about four days, he barely slept and often went without proper meals as he struggled with the portal. He was told registration would open by 1 a.m., so he stayed awake after fully charging his devices. When the time came, the registration link did not appear until about 5 a.m. Even then, the process repeatedly failed. He created eight email addresses, but none received the confirmation link needed to begin registration. He later created ten more, with the same result.

By around 7 a.m., he went to a cybercafé for help, but the problems continued. Each time he entered his JAMB number, the system returned an error and refused to move forward. From midday until late evening, he kept trying without success. He returned home around 9 p.m., exhausted and hungry, and continued the process on his phone and computer, with help from the café operator. It was not until about 1 a.m. that he was finally able to enter his details and create an account.

The difficulties persisted the next day. When he returned to the cybercafé for biometric thumbprinting and to upload his signature and state he had visited, the portal again failed repeatedly. He spent the entire day stuck at the same stage due to error messages. Abubakar eventually completed his registration around 1 a.m. on the third day. “I went through three to four days without proper sleep or food,” he said. “It affected me emotionally and financially. Nigeria can do better.”

After School, Job Applicants Lose Opportunities to ICT Failures

Umar Bafashi, a graduate of Public Administration, applied for recruitment into the Nigeria Customs Service. As part of the process, applicants were required to write a pre-test exam before moving to the next stage. The exam was scheduled for 9:00–10:00 a.m., but he could not access the portal until about 9:25 a.m. because it was not responding. He eventually wrote the exam, but two days later, he received a message stating that he was not qualified to proceed to the next stage. He said the experience left him sad and discouraged.

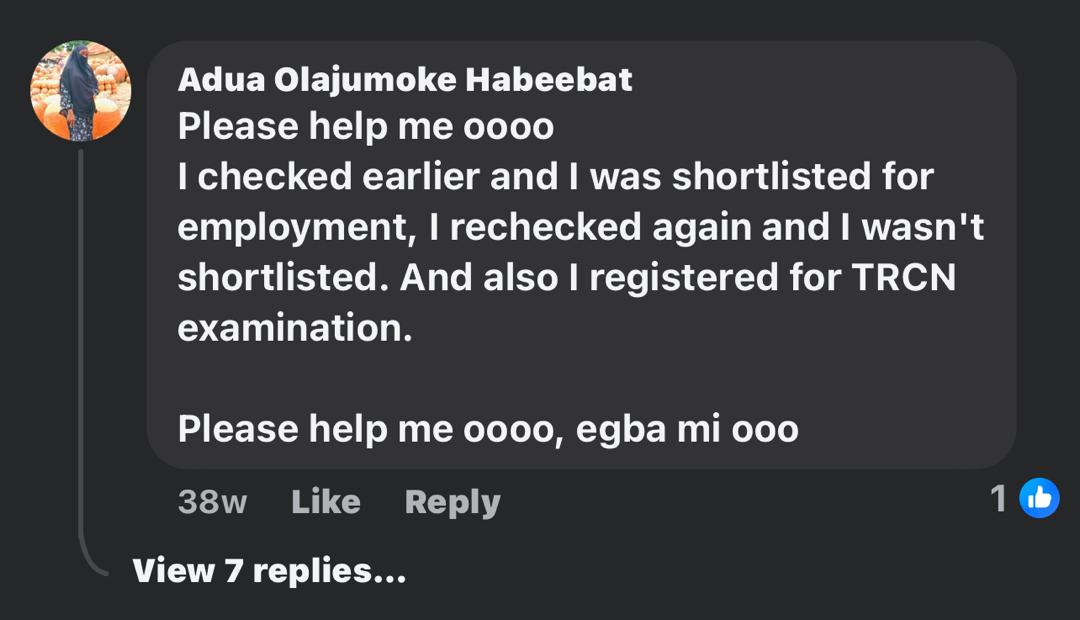

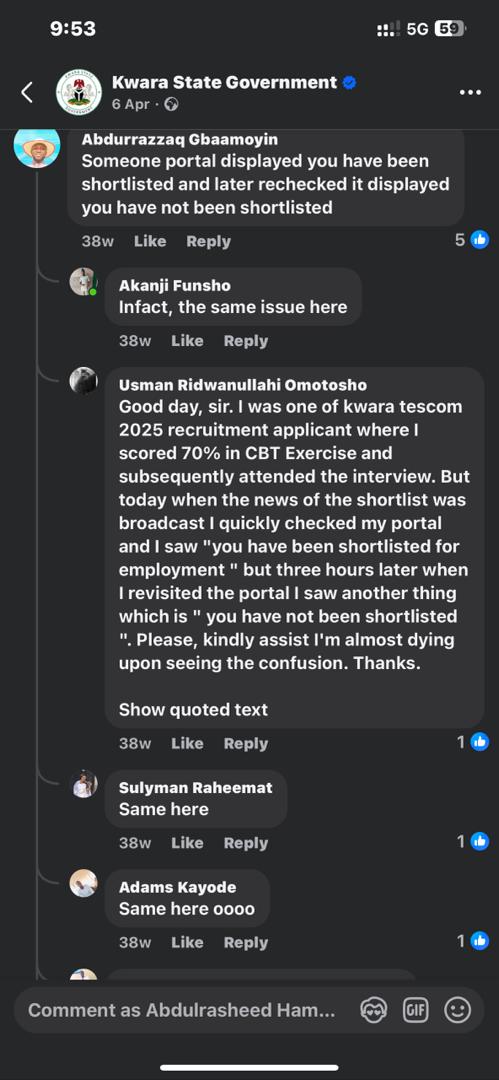

Screenshot of applicants expressing frustration after initially being shortlisted, then checking the portal again to find they were no longer shortlisted

Sani Sa’ad, a Nigeria-based lawyer, also shared a similar experience involving a friend. According to him, his friend was scheduled to write the Nigeria Customs Service pre-test exam at 3:00 p.m. and was fully prepared. However, the website failed completely, making it impossible for her to access the exam. “She sat for over an hour refreshing the page, but nothing worked,” he said. He added that it was troubling that in 2025, such an important national recruitment exercise could still be disrupted by system failures, raising concerns about fairness and accountability.

Screenshot of applicants expressing frustration after initially being shortlisted, then checking the portal again to find they were no longer shortlisted

Screenshot of applicants expressing frustration after initially being shortlisted, then checking the portal again to find they were no longer shortlisted

Similar issues were reported during the Kwara State Teaching Service Commission (TESCOM) recruitment. Usman Ridwanullahi Omotosho, one of the applicants, said he successfully wrote the CBT exam and scored 70 percent. When the list of shortlisted candidates was announced, he checked the portal and saw that he had been shortlisted. Three hours later, when he checked again, it showed that he had not been shortlisted. He said the sudden change left him emotionally distressed. The Kwara State Government later described the incident as a technical glitch, but many applicants said the experience caused serious emotional strain.

Screenshot of applicants expressing frustration after initially being shortlisted, then checking the portal again to find they were no longer shortlisted

Nigerian Law School Is Not Excluded

Idris Mansur said his frustration as a bar aspirant continued even after passing his Bar final examination. During the clearance process, he filled the required form, but days later, he discovered that his passport photograph and signature had been replaced with another bar aspirant. He filled the form again, but the same problem occurred.

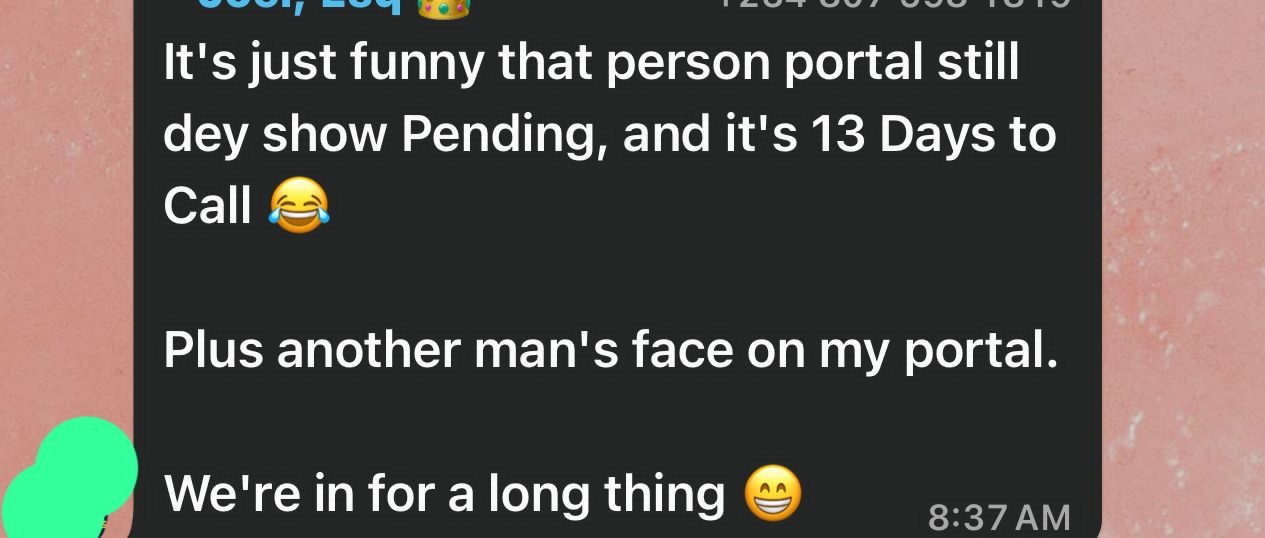

Bar aspirant lamenting how his portal was still showing pending and showing another man’s face 13 days to their call to bar.

It was only after completing the process for the third time that he was finally cleared for a call to the bar. He said many bar aspirants across the seven Law School campuses faced similar issues.

Idris Mansur’s profile with another applicant’s passport and signature

Similarly to Idris, Adewale shared his experience of prolonged portal-related problems at Olabisi Onabanjo University (OOU) that eventually denied him his certificate after eight years of studying Law. According to him, the issues began at the 300 level when the university switched from the RecordSoft portal to the OOU portal without proper notice to students. Under the old system, students could pay 60 percent of their fees and complete the balance later. However, after the transition, records of the 60 percent payment disappeared, and many students were barred from writing examinations.

He said he wrote several letters and visited different offices before he was eventually allowed to pay again. Even after payment, he could not print his course form, and some courses he had passed appeared as carryovers on the portal. He explained that he had to search for results across other faculties and submit them manually to the ICT unit. In his final year, he was told he did not write the continuous assessment for a course he had already passed even though he sat for it. Despite repeated complaints and appeals, the issue remained unresolved until a professor intervened and took him to the course adviser, who promised to include his name on an approval list. When the list was released, his name was missing, and the course adviser later told him he had forgotten.

Adewale said he continued writing letters and visiting the university for years, meeting different deans who promised to resolve the issue. During this process, he was informed that his studentship had been terminated. He explained that although he was supposed to graduate in the 2012/2013 session, the unresolved portal and record issues forced him to take multiple leaves of absence, including periods when he could not afford to continue. He said that since then, the university has repeatedly told him he is no longer a student, adding that without his certificate, his hope of practising Law was shattered.

Some Universities with Technical Problems

On June 3, 2025, the Federal University of Technology Akure (FUTA) temporarily closed its student portal due to technical issues affecting payments and course registration.

As of November 14, 2025, students at the National Open University of Nigeria (NOUN) reported being unable to access eLearning and academic portals for weeks, preventing them from accessing course materials, Tutor-Marked Assignments (TMAs), and other essential academic functions.

Ahmadu Bello University (ABU), Zaria, also announced a portal outage caused by internet service disruptions linked to its provider, Globacom, affecting normal portal use.

In October 2025, prospective students of the University of Abuja (UNIABUJA) expressed frustration on social media over delays, technical errors, and poor communication during the 2025/2026 admission exercise, prompting a response from the admissions office.

Beyond Nigeria: The Same Portal Failures Plague African Universities

Portal and digital system problems are not limited to Nigeria. Across Africa countries, students face issues such as portals crashing, slow or inaccessible systems, incomplete records, and failed submissions.

On August 6, 2025, the West African Examinations Council (WAEC) temporarily shut down its result-checking portal hours after releasing the 2025 WASSCE results, affecting students across member countries.

Paa Kwesi Perry, a distance student at the University of Education, Winneba in Ghana, said she could not access her results on the portal. She also experienced registration issues even after fully paying her fees.

Students at the University of Liberia protested over e-portal problems disrupting registration, scheduling, access to results and academic activities.

The University of Ghana had to cancel online Interim Assessments (IA) and suspend online lectures due to ongoing internet disruptions. On March 14, 2025, internet connectivity across the country was affected by damage to undersea fibre optic cables.

At the University of Sierra Leone, transition to online systems has been hampered by poor internet connectivity and limited ICT infrastructure, meaning students struggle with accessing digital learning platforms, downloading content, and using apps designed for courses.

Civil society reports on Côte d’Ivoire note network infrastructure issues at several public universities including interruptions in internet links, which affect students’ ability to use online portals and digital research tools on campus.

In Kenya, the Higher Education Financing Portal used for student loans and funding applications was taken offline for an extended maintenance period during peak application windows, leaving applicants unable to submit or access applications.

In Mumbai (India), a university portal shutdown left hundreds of first-year students unable to register through the online system when it abruptly closed mid-cycle.

Experts react

Ibrahim Bashir Aliyu, an ICT expert explained that recurring glitches in examinations, recruitment portals, biometric systems, and university platforms are caused by systemic and structural failures, not isolated incidents. Many problems stem from outdated ICT infrastructure, weak network capacity, unstable power supply, and insufficient system testing before deployment. For example, computer-based exams like CBT and UTME run on local servers and rely on obsolete devices, which often malfunction during power interruptions, forcing candidates to restart or lose time. Additionally, technical staff at many centres lack the expertise to quickly resolve issues, while some students struggle due to low digital literacy, compounding the impact of system failures.

Aliyu said similar challenges occur at the university level, where student portals frequently crash during peak periods such as registration, fee payment, or result checking. Many universities use outdated software, poorly maintained databases, and low-budget vendors, creating systems that cannot handle large numbers of concurrent users. On national platforms like the NYSC portal, the lack of scalable architecture and redundancy means that when one server fails, the entire system becomes inaccessible. He stressed that pre-testing and proper planning are often ignored, leaving students to face incomplete transactions, failed payments, and inaccessible records.

Biometric failures during NYSC clearance, Aliyu noted, result from outdated devices that no longer meet modern performance standards. He added that Nigeria has qualified ICT professionals, but institutions often fail to employ or properly engage them, instead cutting costs or relying on underqualified vendors. Aliyu concluded that unless institutions invest in modern infrastructure, skilled personnel, scalable system design, proper testing, and continuous upgrades, ICT failures will continue to disrupt exams, recruitment, and academic processes, affecting thousands of students across the country.

Muhammad Auwal Ahmad, CEO of Flowdiary, an innovative AI-powered edtech start-up and ICT expert, said most of the problems are caused by network glitches, which are common in the country. He explained that portals often fail when they cannot handle high traffic. “As a tech person, I see this as low server bandwidth, because most portals use shared hosting,” he said.

He added that many digital challenges come from unstable networks and systems that cannot manage heavy traffic. Most portals lack proper load balancing, which affects performance when many users access them at the same time.

Ahmad said the solution is to adopt scalable cloud infrastructure and modernise systems. “Using powerful, fast servers and scalable platforms can improve bandwidth and allow portals to handle high user traffic reliably,” he explained.

According to a 2023 study by Dupe S. Ademola-Popoola and colleagues on the status and challenges of ICT network services in Nigerian universities, inadequate ICT infrastructure remains a major barrier to effective higher education delivery. The research, which examined 25 higher education institutions across Nigeria’s six geopolitical zones, found that poor internet bandwidth, unreliable power supply, and limited technical expertise severely undermine access to digital services. The average internet bandwidth per student was just 0.038 Mbps, far below international standards, while 35% of institutions relied on costly generators for power backup. Smaller institutions were particularly affected, with bandwidth constraints worsened by dependence on third-party ICT managers and weak in-house technical capacity. The study recommends significant bandwidth expansion, adoption of renewable energy solutions, and systematic training of internal ICT staff to improve sustainability, reduce costs, and enhance system reliability. Implementing these measures, the researchers argue, is critical to closing Nigeria’s digital divide and strengthening the global competitiveness of its universities.